Resident physiotherapy expert

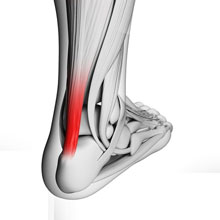

Achilles Tendinopathy is the most common problem amongst runners with it accounting for between 6-17% of all running injuries. A quick google search reveals 101 ways to treat it and you could probably come up with a few more if you ask anyone who has experienced it!

Causes of Achilles Tendon Pain

Over the years there has been much debate over the cause of chronic Achilles Tendon pain and as a result mixed views on how best to treat the symptoms, with variable results. Initially, we believed that the pain was due to an inflammatory process referring to the symptoms as ‘Achilles Tendinitis’. Treatment would have been a combination of corticosteriod injection, a course of ‘NSAID’s’ such as inbuprofen, physio would have been ultrasound, frictions (to breakdown ‘adhesions’), taping, heel raises and rest (from the aggravating activity).

Studies have since shown that there is an absence of inflammatory cells (these initiate the start of the inflammatory process) and inflammatory mediators (responsible for the clinical signs, swelling, heat, pain & changes needed for healing process to happen) in tissue samples of Achilles Tendons several days after rupture and postmortem (1)(2)(3). These findings have lead many other authors to the hypothesis that Chronic Achilles Tendon pain and ‘injury’ is a result of a degenerative process, possibly because of the collagen’s (which forms the basis of the tendon structure) inability to adapt to change in load or due to a being subject to a constant load that exceeds the repair capabilities of the tissue (4)(5). “A mismatch between mechanical loading and adaptation” (3). The collagen structure in these painful tendons is ‘haphazard’ or ‘irregular’ making it less effective at coping with load and prone to overuse injuries (1)(2).

More recently, studies of chronically painful Achilles Tendon tissue have shown there is additional ingrowth of blood vessels and nerve endings – known as ‘neovascularization’ and it has been proposed that this may ‘predispose’ an individual to a chronic problem. However, an editorial review by Johnannes et al (6) of the literature in relation to this suggests that at this present moment in time there is no real evidence to support this theory. It has also been demonstrated that a powerful neurotransmitter (brain chemicals that transmit messages through the body to the brain and back!) called ‘glutamate’ is present in chronically painful Achilles Tendons (2)(7)(8). Glutamate is an ‘excitatory’ neurotransmitter which stimulates the brain resulting in you experiencing pain.

Oxygen usage in tendons is 7.5 x lower than muscles! (9). This very well developed ‘anaerobic’ (the ability to produce energy without the use of oxygen) capacity in tendons means they are able to sustain load and maintain tension for prolonged periods. However, the blood flow to the tendon reduces with age and mechanical loading (10). The combination of these can lead to slower healing / recovery following injury (11).

Causes of chronic tendinosis are categorised as either (1) intrinsic – tendon alignment (how straight it is) which can be affected by excessive pronation (flattened arch of the foot) or supination (higher foot arch), ‘bowing’ in or out of either the knee or ankle joints. Tight muscles or muscle imbalance in the hamstrings, reduced strength or endurance capabilities in the calf muscle. (2) extrinsic – change in footwear or training patterns, poor training technique, previous injuries such as ankle sprains and training surfaces. If we consider that forces through the Achilles Tendon can be up to 12.5 x our body weight when running (14), it doesn’t take much imagination to understand the potential effect on the tendon if any of the intrinsic or extrinsic factors are present.

So how do we treat chronic Achilles Tendon Problems?

Well ‘eccentric loading’ exercises proposed by Alfredsson (12)* have consistently been shown in the literature to provide the best improvement in both pain and function, although the exact mechanism of how these exercises work is not fully understood. ‘Eccentric loading‘ (loading the tendon as it lengthens under tension) is the opposite to ‘concentric’ which is how we normally train our muscles. So instead of performing a ‘calf raise’ exercise where we would rise up onto our toes and shortening or contracting the muscle (and tendon!) we do the opposite. It is believed that the exercises ‘normalise’ the tendon structure, establishing ‘homeostasis’ (maintains ‘stable’ state) which is disturbed in ‘overuse’ and overload injuries (13). Eccentric loading over a prolonged period (> 11 weeks) stimulates ‘collagen synthesis’ (new collagen) or remodelling of the collagen. This results in new stronger collagen which is no longer ‘haphazard’ in structure, reducing the risk of overload (12)(3).

Clinically, I have used these strengthening exercises alone with some degree of success and would certainly give them out as part of any Achilles Tendon treatment programme. Along with the reassurance that it is normal for results from this exercise alone to take time, 3-12 months! However, these exercises alone do not address all of the intrinsic or extrinsic factors that may have caused the symptoms initially. In my experience a thorough biomechanical assessment is key to ensure that we address other factors, such as stiff feet and ankles, poor balance and ankle stability and less than efficient or effective running technique!

Jenny Manners MCSP, PgCert

Principle Physiotherapist, Meadowhead Physiotherapy.

*Lowering heel slowly over the edge of a step, initially knee straight then with knee bent with a gradual increase in load. The exercises are performed 15 x3 (twice a day) initially for 12 weeks, but for 6-9 months further if improvements have been shown. It is acceptable for a low to moderate amount of pain to be experienced during the exercises and some authors suggest that this is an important part of the rehab process.

References – Full references provided on request

(1) Movin et al (1997)

(2) Alfredson et al (1999)

(3) Langberg et al (2007)

(4) Jozsa et al (1990)

(5) Astrom & Rausing (1995)

(6) Johnannes et al (2012)

(7) Alfredson et al (2002

(8) Alfredson (2005)

(9) Vailis et al (1978)

(10) Astrom (2000)

(11) Williams et al (1986)

(12) Alfredson (1998)

(13) Langberg et al (2001)

(14) Komi et al (1992)